1913

Niels Henrik David Bohr was born in Copenhagen on October 7, 1885, as the son of Christian Bohr, Professor of Physiology at Copenhagen University, and his wife Ellen, née Adler. Niels, together with his younger brother Harald (the future Professor in Mathematics), grew up in an atmosphere most favourable to the development of his genius – his father was an eminent physiologist and was largely responsible for awakening his interest in physics while still at school, his mother came from a family distinguished in the field of education.

After matriculation at the Gammelholm Grammar School in 1903, he entered Copenhagen University where he came under the guidance of Professor C. Christiansen, a profoundly original and highly endowed physicist, and took his Master’s degree in Physics in 1909 and his Doctor’s degree in 1911.

While still a student, the announcement by the Academy of Sciences in Copenhagen of a prize to be awarded for the solution of a certain scientific problem, caused him to take up an experimental and theoretical investigation of the surface tension by means of oscillating fluid jets. This work, which he carried out in his father’s laboratory and for which he received the prize offered (a gold medal), was published in the Transactions of the Royal Society, 1908.

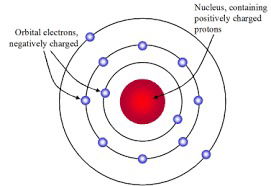

Bohr also contributed to the clarification of the problems encountered in quantum physics, in particular by developing the concept of complementarity. Hereby he could show how deeply the changes in the field of physics have affected fundamental features of our scientific outlook and how the consequences of this change of attitude reach far beyond the scope of atomic physics and touch upon all domains of human knowledge. These views are discussed in a number of essays, written during the years 1933-1962. They are available in English, collected in two volumes with the title Atomic Physics and Human Knowledge and Essays 1958-1962 on Atomic Physics and Human Knowledge, edited by John Wiley and Sons, New York and London, in 1958 and 1963, respectively.

English chemist Frederick Soddy proposed in 1912 that the same elements exist in different forms, with nuclei having the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons. His theory of isotopes (a word he coined from the Greek, meaning "in the same place") explains that different elements can be chemically indistinguishable but have different atomic weights and characteristics. As an example, uranium 235 and uranium 238 are two different isotopes of the same element, uranium, one with 235 protons and neutrons in its nucleus, and the other with 238. In 1920 he showed the importance of isotopes in calculating geologic age, which led to development of carbon-14 dating. Soddy's theory of isotopes (now known to be true) was controversial among scientists until James Chadwick's discovery of the neutron in 1932.

His other work was also of importance in early 20th century chemistry. In collaboration with Ernest Rutherford in 1903 he showed how radioactive elements disintegrate, in a study that introduced the concept of "half-life" for radioactive decay. With Sir William Ramsay in the same year, he demonstrated that decaying radium produces helium. He is also credited for discovering the element protactinium in 1917.

Soddy gradually quit science in frustration after winning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1921, and turned his attention to economics, arguing in papers and books that ethics and morality should be as fundamental as supply and demand in economics. He maintained that science had progressed enough to provide food and health care for all the world's inhabitants, but that the monetary system effectively prevents distribution of this abundance by peaceful means. In 1936 he retired, after the sudden death of his wife. They had no children, a factor Soddy attributed to exposure he had endured before the risk of radiation was fully understood.